For the first time on my trip I felt cold. Waking up to the spectacular view from my room at ‘The Fox and Hounds’ I noticed a wall thermostat and radiator. The climate here felt like it was going to be what everyone had warned – distinctly British. It was January, the Southern Hemispere’s midsummer and someone somewhere had said it’d be jersey weather. However, today it wasn’t; today turned out to be unusually warm.

Stewarts Bay. Seawater and not much tide. Noisy Kookaburras somewhere in those trees

It was my first morning in Tasmania; the night before I’d made it across the Eagleneck peninsula to within striking distance of the old settlement of Port Arthur. I could go into some general guff here about First Governor, Crims, British Rule and aboriginal mis-treatment, but for the moment, here, I was looking out at the view above. From the ‘Fox and Hounds’ pub. It transpires that the British had introduced the fox as a ‘good idea’ for the hunting types who didn’t want to miss out on a ‘gentleman’s pastime’ etc., etc., when arriving in the Colonies.

Now anything ‘alien’ is treated with caution and much of what was ‘introduced’ is being systematically removed. That goes for thistles and weeds that came in grazing fodder, fennel from the Mediterranean, a 101 garden plant types, Crows, Bunnies, wild pigs, sheep and the army of other nasties that have got the better of native species over the years. Not that the original settlers were to blame. In the 1830s or 40s you did what you thought best to survive – thrive even. Australia [and NZ] are wastelands of what they once were, with sheep still being ever present.

Why wouldn’t you re-create your new world in the image of what you knew? Hampshire, the Fells, Devon or Huntingdonshire?

Cleared land looks normal but 175 years ago was forest

At about the same time, the British Government – along with its able advisors and the patronage of King George III himself [and then his son GIV], set up a base in Tasmania almost more, it seems, with the idea of ‘stopping others’ rather than making it a useful thing for Empire. Of course history shows it did both. Mr Tasman, the Abel Dutchman, had merely sailed through these parts years before but failed to make any meaningful claim to the territory; the French came and went naming a few bits; but it was the Brits who thought ‘we’d better have this…’ and started the first colony. Remember the British up til then [and long after] had been particularly adept or lucky at carving up the world the moment they learned how to chart a map or use a compass. Look at what they got compared to what their rivals got… so they bagged it. The Americas had ‘just’ gone, and losing those territories must have had a huge impact on Imperial morale.

Port Arthur as designed for penal use. Few left this place

Tasmania in the eyes of the coloniser, needed to be exploited. The island had unimaginable resources and hardly anything in the way bar ‘a light scattering of savages’. But it looked like hard work – years possibly before there’d be a yield worth reporting. So, the brainchild of deportation, transportation or penal settlement was conceived.

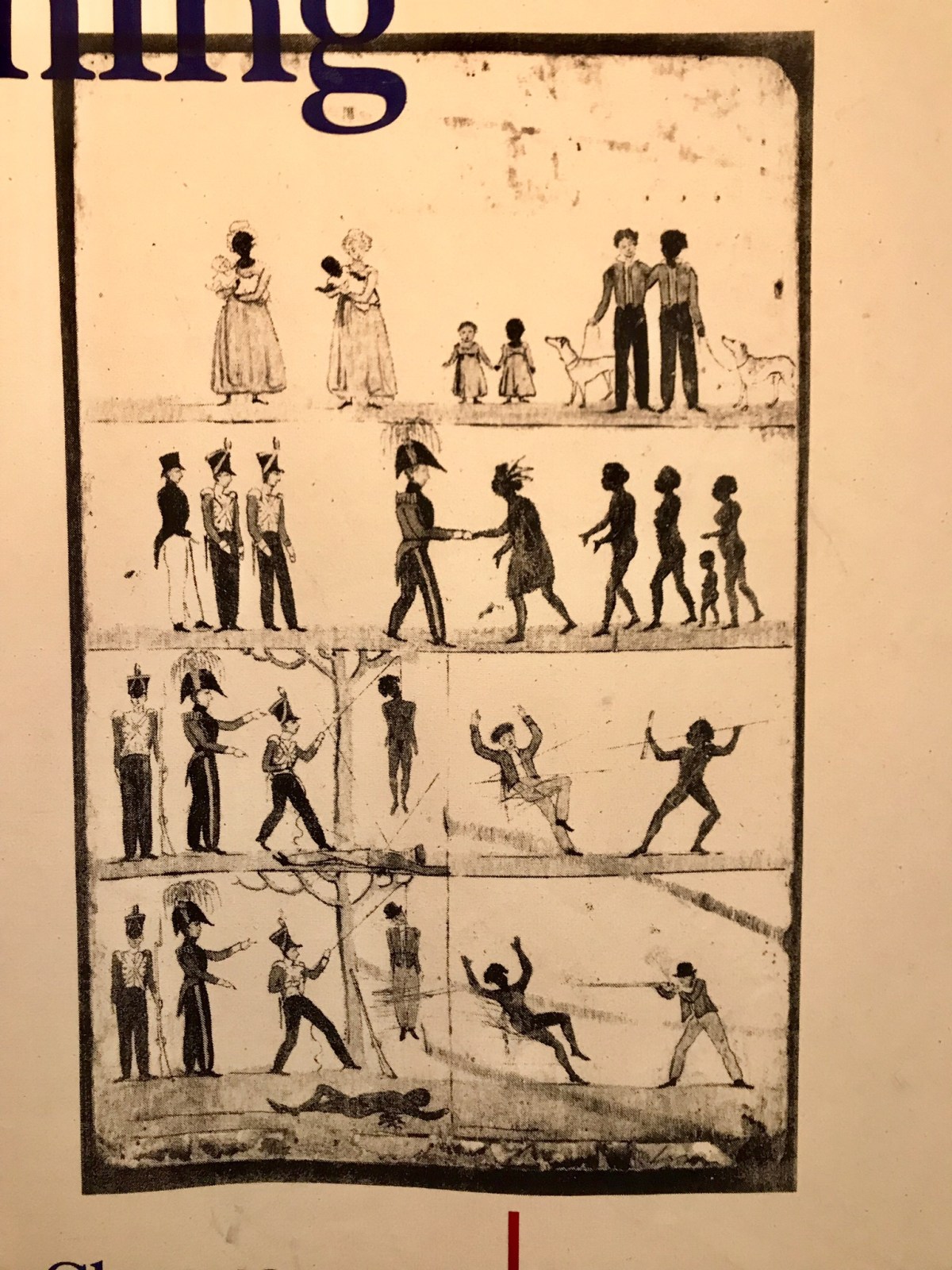

British justice made easy to understand for the indigenous…

And here they came; Britain and Ireland’s worst. The ones that escaped the death penalty at home.

Examples of the timber the Empire’s navy needed [and for every aspect of general construction]. 50m, straight, just growing yards from the beach

Little Dockyard. 175 years ago this lawned area was the sight of the [very accomplished] ship works. Criminals working in 12 hour shifts

The Island of the Dead. 600m offshore where convicts and non-offenders were buried. Current estimates say 1300 lie here

The Island of the Dead. 600m offshore where convicts and non-offenders were buried. Current estimates say 1300 lie here

Port Arthur was established and soon became a burgeoning centre, driven by the efforts of up to 1000 convicts labouring under awful conditions. Timber, boats, minerals were all suddenly a bi-product for this little enclave 12,000km from home. A sentence here meant many things, but for all but a few, escape wasn’t an option – they were on a remote peninsula backed by impenetrable jungle, surrounded by deep sea, sharks, currents and not a sympathiser for hundreds of miles. And they didn’t know where they were. The geography meant no confinement was necessary.

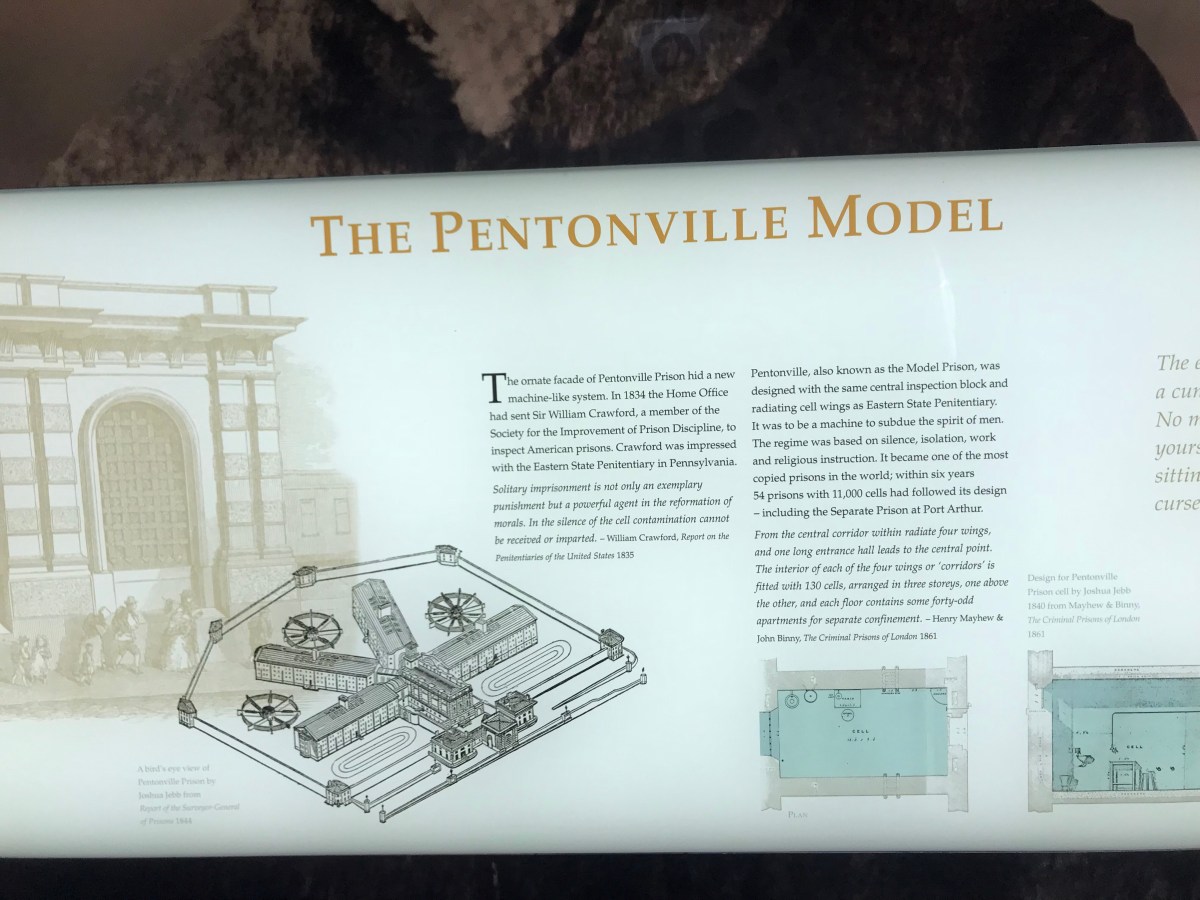

Guides said that the whole event [World Heritage etc.] was worth a visit as long as 2 days. The ticket I’d bought had a 2 day admission, but by the time I’d looked into the ‘Pentonville Model’ [from the London prison], got to understand the effect on the prisoners of the Cat o’nine tails versus solitary confinement, and imagined what living permanently in chains must have been like; it was time to move on. Not 2 days I would say. 4 hours?

A gruesome fact about Port Arthur, that was elided by the guide, was that this was the the site of Australia’s biggest mass murder, when in 1996 a gunman killed 35 people and wounded 21 others. No mark or memorial was to be seen. It happened 6 weeks after Scotland’s Dunblane.

Roiling sea near the entrance to Port Arthur

Almost what fascinated me more was the fact that the convicts were pretty much allowed to exist free in their encampment. No walls or evidence of containment – the geography was enough. On the rare occasions that someone escaped, it was always assumed that they’d attempt to cross the ‘neck’ a long low 50m wide strip of dune land that connected the penal colony with the mainland. It was perceived as the weak spot by both captors and captives. A leak that needed blocking.

The Dog Line

After much scratching of heads the British authorities cleared a strip across this dune land and filled it with crunchy sea shells. Then they tethered 9 ferocious dogs across the 50 metre gap. The idea being that any attempt to get away by a convict would mean they’d pass this way sooner or later. Noise on gravel, and the hounds would start barking. Well that’s what happens when the postman comes at home.

Lazy dogs were replaced with more vicious ones, and the number increased to 18. Some were tethered on stilted platforms out in the shallows in order to detect an escape by wading across.

The only record [I saw] of a convict passing the line unscathed was of a man who actually did it twice before recapture in the bush on the mainland. Must have had a way with animals.