I was driving up Norway’s coastal E6 route, through its most extreme northern region; on my way to the little port of Alta. It was a staging post for the route north to visit Nordkapp at the top of Europe. (A popular if not odd thing to do). It was mid-August and already the daylength had diminished to around 22 hours [the other 2 being just dimness]. Scandinavia is strictly 24 hours ‘headlights on’ when driving, but it seemed odd when it was still perfectly light at 11pm.

At the head of the last fjord before Alta I passed this rusting mess [above] on the roadside. 24 hours later I was back on the ‘Tirpitz Trail’, having discovered that the fjord in front of the town had been the location of some of the most extraordinary and violent episodes in Norway’s wartime past.

Altafjord seen from the harbour in Alta. There must be many days of the year when the weather is grimmer than this

Altafjord seen from the harbour in Alta. There must be many days of the year when the weather is grimmer than this

The ‘What to do in Alta’ list scarcely fills an iPad page; with the new cathedral* coming top, the ‘Heritage Museum’ a close 2nd and something about shopping third. Such is the dirge of this high latitude outpost that it goes on to claim the best views of Aurora Borealis in the whole wide world (me being there in August meant that there was virtually 24 hours of daylight so not possible). Having already driven 1500 km through the Arctic, I realise that that claim is made by virtually every town, village and hamlet across Norway, northern Sweden and ALL of Finland. All quite understandable when it’s that or making boasts about sauna culture, reindeer sledging & salmon fishing.

*’New Cathedral’ status is slightly controversial since Alta is only a smallish town. Although dubbed ‘Northern Lights Cathedral’, its accepted status really means that it is a church. Architecturally quite stimulating, and clearly more impressive at a time of year when the Northern Lights are doing their bit. For a while it had nearby Tromsø worried sick that the Most Northern Cathedral status might have shifted North. They needn’t have worried in the long run.

At the bottom of my iPad page there was mention of The Tirpitz Museum – a place dedicated to the story of one of the world’s largest ever warships. The museum was located 15 km away in (effectively) someone’s house. Generally it had received good reviews apart from a recent snipe by someone saying 100 NOK was expensive. The reviewer had been swatted back by the owner telling the world about the museum getting no local authority subsidy. [100NOK = +/- £10].

Reading on; I realised that this little corner of the fjord housed a unique place that would unravel the mystery of those rusting roadside relics and what had happened there 75 years ago.

I headed to the museum – and 90 minutes later was back at the rusting relics studying the scene with new knowledge.

Abandoned anchor that belonged to one of the smaller protection vessels

Abandoned anchor that belonged to one of the smaller protection vessels

The 1930s saw Germany’s response to its defeat in World War 1 – all of Europe felt it, and as history recounts, little was done. Tirpitz was one of the two massive ‘Kriegsmarine’ ships built in order to ready the country for the conflict ahead. Bismarck was the other. Construction of both was started in 1936, and 4 years or so later these behemoths were ready for action.

Archive shot of Tirpitz in Kaafjord a little inlet off Altafjord

Archive shot of Tirpitz in Kaafjord a little inlet off Altafjord

Kaafjiord today – the ship in the earlier photograph would have been moored where the white buoy [mid left] is just visible

Kaafjiord today – the ship in the earlier photograph would have been moored where the white buoy [mid left] is just visible

All historical records tell you of the enormity of these two ships – in the most extraordinary detail. Faster, impregnable [the steel ‘belt’ at the girth was 320mm thick to prevent holing at the water line], and of course bigger guns than anything seen before. All in all these ships were amongst the most feared weapons of War that had ever been seen in the European arena.

The story of these two ships took them to very different places, but both eventually suffered the same fate, being hounded by the Allies until the very end.

Tirpitz was primarily involved in the task of stopping shipping entering or leaving the northerly waters around the cape of Norway. Strategically preventing Allied shipping from getting in and out of Northern Russia and the crucial port of Murmansk.

Tirpitz was primarily involved in the task of stopping shipping entering or leaving the northerly waters around the cape of Norway. Strategically preventing Allied shipping from getting in and out of Northern Russia and the crucial port of Murmansk.

Above: The Barents sea from the most Northern point in Europe. On a good day. Arctic convoys on the Murmansk run had to chart a route 300km north of this location around Bear Island in order to escape the range of enemy aircraft.

In Memoriam

In Memoriam

Almost before her life had begun Tirpitz was challenged by never having the chance to flex her muscles on the open sea. Armed with long range guns [15 inch] – that in practice had ‘hit’ dummy targets regularly from 25km, she was forced into a life of dodging the dozens of Allied attempts to destroy her.

Kaafjord in Norway was a place that played its part in history. The German monster entered the occupied territory in Arctic Norway where she lived for nearly two years evading constant attack and harassment.

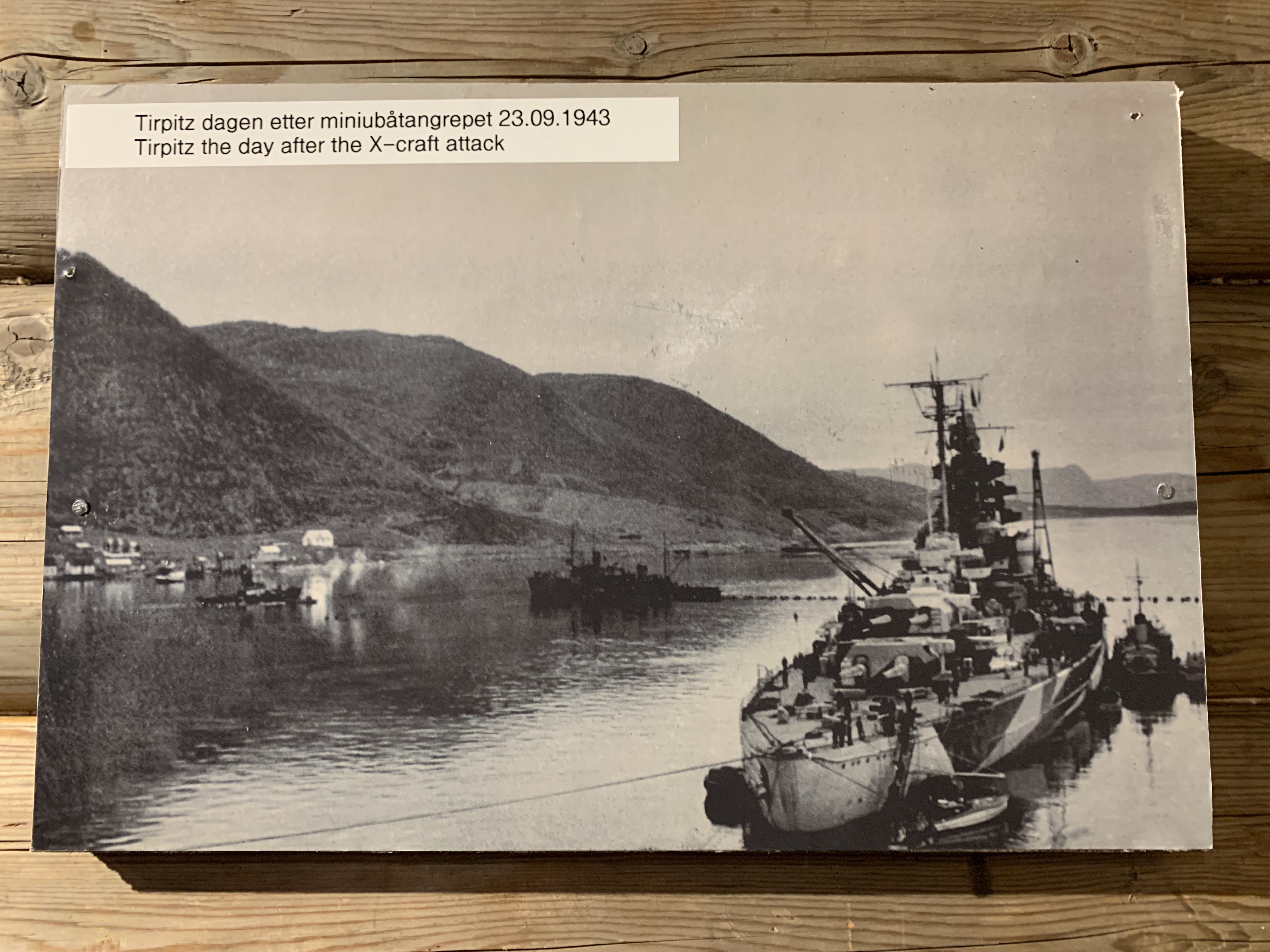

Above: Still moored but damaged after the fabled attack by British mini-subs in 1943.

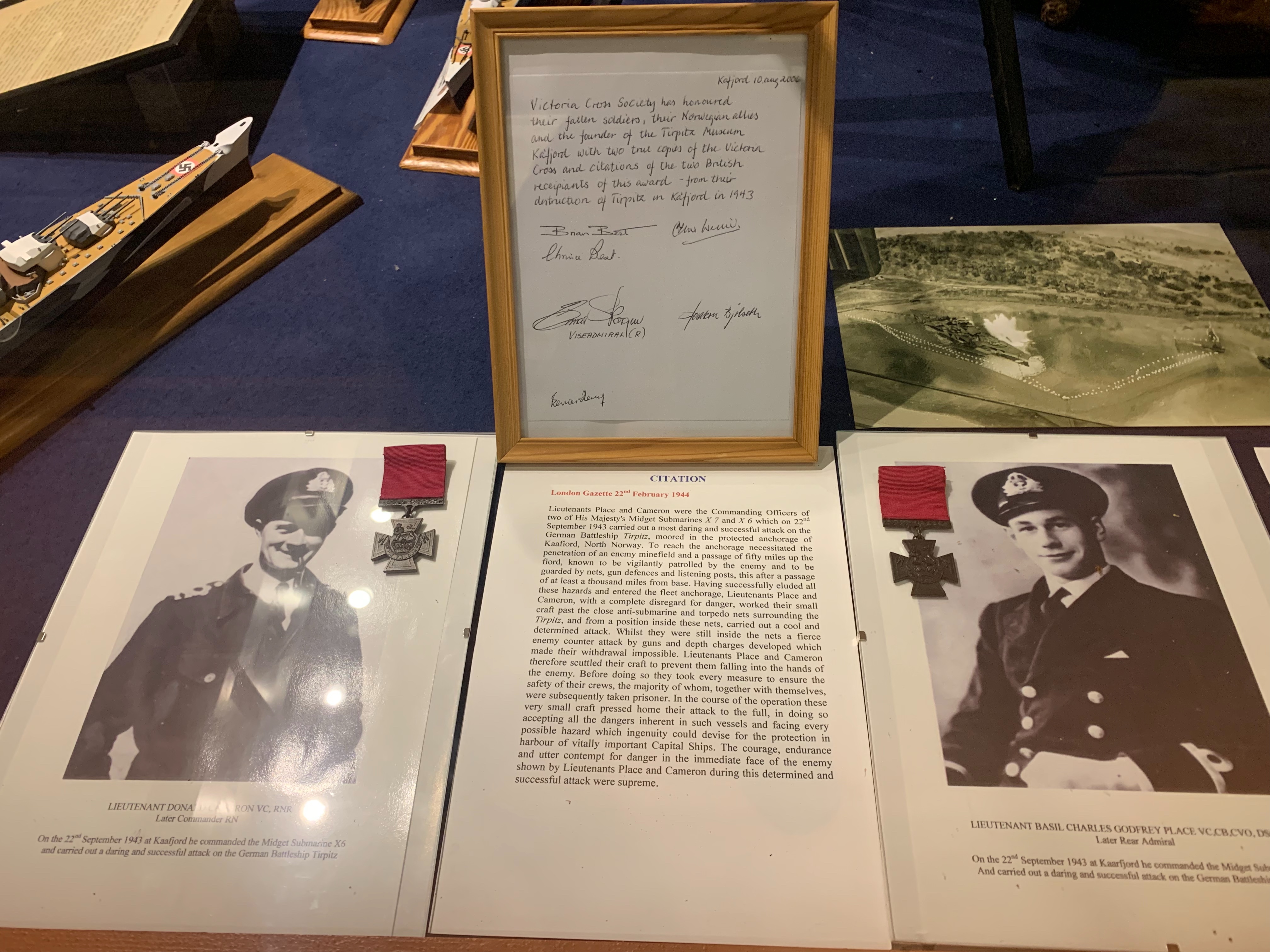

Below: Citation and testimony to Lieutenants Place and Cameron who headed the X Craft attack. Both survived and both were awarded the Victoria Cross.

My little trip had taken me to Tirpitz’s lair where she survived; penned from torpedo attack, defended by anti aircraft batteries and hundreds of deadly mines.

Nearby rock scree slopes are still littered with smoke canisters that the German defences used to cover the area in cloud so as to evade the aim of bomber raids.

There were 7 Allied attacks made on Tirpitz and her defence ships in Kaafjord between April 1944 and September of the same year. Operation Paravane, involving 28 Lancasters flying from a Russian base attacked the Tirpitz on 15th September 1944.

Below: 12,000 lb ‘Tallboy’ being loaded onto a Lancaster bomber

Above: A Lancaster crossing the fjord as it is rapidly obscured by a smokescreen. 15th September 1944.

Above: A Lancaster crossing the fjord as it is rapidly obscured by a smokescreen. 15th September 1944.

Operation Paravane was considered a success. Despite the number of 12,000lb bombs dropped it took only 1 to disable the mighty ship. Effectively the damage was mortal, and Tirpitz would never make it to the open seas again.

Author’s view from a crater caused by a Tallboy ‘near miss’. The ship was only a matter of metres away

The tiny church at the head of Kaafjord. It’s recorded that the German dead from the numerous air raids are not buried here – there is an unmarked cemetery on a nearby hillside that is their resting place. In this church yard are the graves of some of the brave Norwegian resistance who provided invaluable ‘info’ about the ship moored on their shores. Resistance people to whom the free world owes a debt…

Over the next 2 months rapid repairs were made to the ship, scrapping the damaged gun emplacements and fixing the huge gash in her side.

[In this remote fjord the wreckage from the repairs was just dumped on the shore. Although the seasonal weather may seem extreme to those who don’t live in the Arctic; there are effectively 2 ‘conditions’ – summer constant and winter frozen. The ageing process isn’t the same as elsewhere with the cycle of dampness/freezing and thawing which corrodes metal far faster. Stuff survives.]

Unable to perform with full capability, Tirpitz was ordered south to Tromsø to act as a stationary battery. From there she was within range of modified Lancasters, which destroyed her on 12th November 1944.

Above: The E6 road, and its story. Below a brass fitting pilfered from the electrical controls of one of the abandoned gun turrets.