In 1771, the celebrated English writer Samuel Johnson visited the remote Hebrides on his historic tour of Scotland – commenting and proselytising as he went. His remarkable journal provides a thorough account of many places on the tour before he reaches, homeward-bound, the Island of Mull; and in particular the small adjoining island of Iona. He makes no apologies in describing a land that ‘was starting to show signs of its loss of innocence’… an arcadia already curling at the edges. ‘A remote and black land with few people and a strange language’… Whether or not his observations were fair, it hardly matters since there are no other accounts of these wild places in the times in which he wrote.

Until about 20 years ago visitors to Mull could probably be forgiven for thinking the same about an ‘arcadia’ and ‘loss of innocence’ as things on the Island would be, to many, much the same as they were in Jacobite times.

Today the Scottish Islands have grown in popularity with visitors to a point where you’d be forgiven for being frustrated at traffic queues, booked-in-advance accommodation, and car parks stuffed with RVs. The last 2 summers [Pandemic 20/21] have furthered the interest from ‘staycationers’ anxious to find pastures new. Mull is no exception, and is, apart from neighbouring Skye, the most accessible.

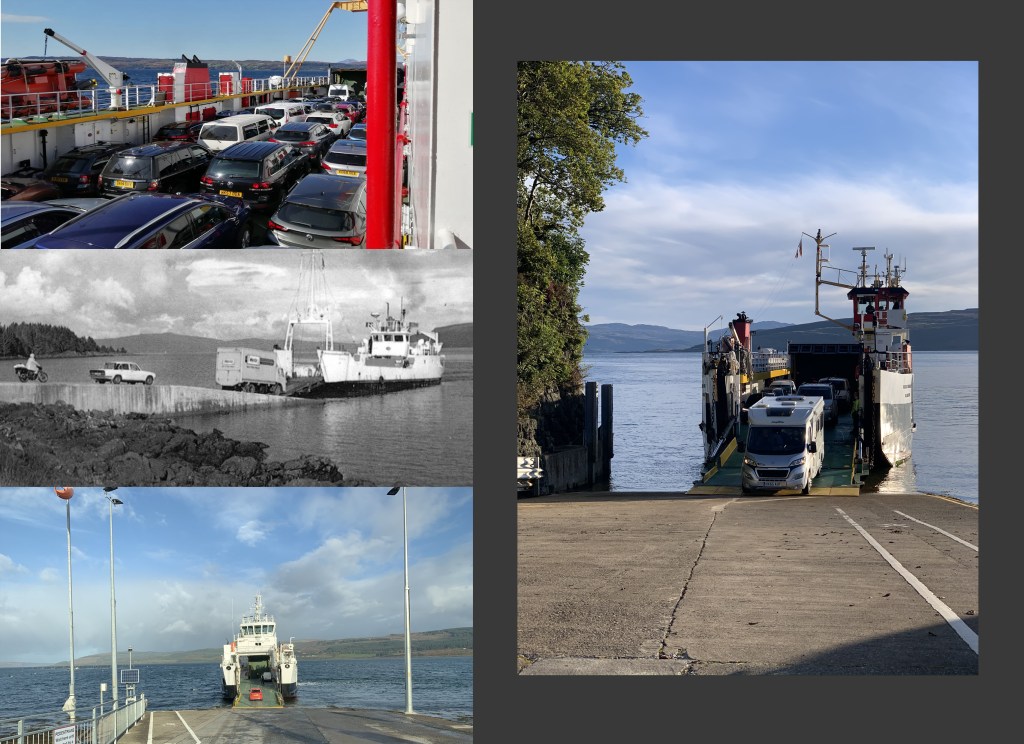

It takes only 40 minutes or so to reach the Island of Mull from the Scottish mainland via one of the regular ferry services which arrive at either Tobermory, Salen or Craignure. In that time you are transported to another world – literally. A landscape that has endured relative isolation and hardship since the pontifications of commentator Johnson 250 years ago.

A quick glance at the map will show you that Mull’s shape is essentially the same as that of the Euro symbol € – only the other way round. ‘A funny shaped island’. Further inspection will show that the road network is simply made up of 2 circuits which circumnavigate the island with both ‘loops’ meeting at the mid point in a place called Salen.

You would be forgiven for thinking Salen was a place of bright lights and fast food. It’s not. There’s a single fuel pump, chainsaw repair workshop, red letter box, campsite, jetty, and a some BnBs. And warnings about otter movements across the main road.

The map loops are essentially one around the North and the other a circuit around the South. It’s more complicated than that when you add in old drovers routes, tracks to remote farmsteads and the long and winding road out to Iona. Most of the roads are manageable, but it helps to choose the time of day you travel… oncoming traffic can become a challenge. Especially if its a big RV.

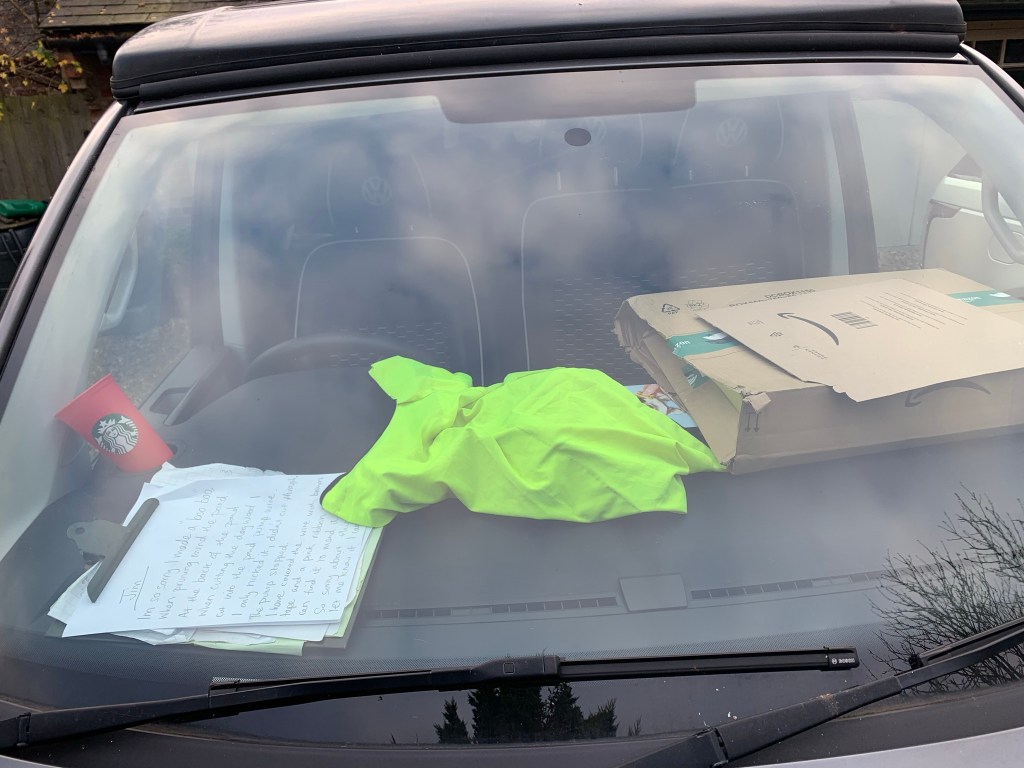

In my experience, in my van, I often travel [solo] wearing a high vis jacket, clipboard in windscreen and a few old coffee cups littering the dashboard: that way you pass for a delivery van, and that curries better favour with on-comers and the impatient locals. Somehow you brooch a subliminal Karma allaying the tendency for Road Rage. People love the idea of a package; it brings a joy that shouldn’t be delayed any more than necessary. Believe me it works.

A mix – Roads to test you.

Although most of Mull’s roads are easily driveable, it’s obvious that they still follow the original paths that must have been formed by the habits of foot travellers and their driven beasts long ago. Sudden gradients, sharp bends and contour-hugging tracks are testimony to the drovers of the past.

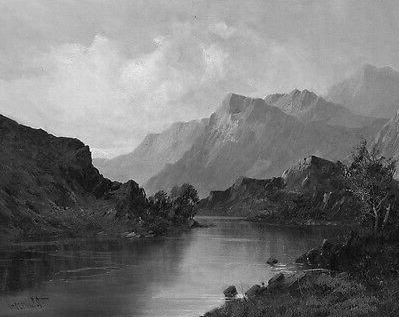

Views of the landscape on an unusually good day.

This is a landscape that was shaped by the great glacial events of the last Ice Age, but if viewed as a canvas, much of what you see has been added to by the events of history on Britain’s mainland. A history that reflects the turbulent times in which those people lived. War and Economics – have we heard this before? There was an English determination to quash Scots Independence which forced dissenters into places they wouldn’t normally choose to go; Mull would have been amongst those places – along with Scotland’s other remote islands and peninsulas. All those years ago on the Mainland, it was a era of fugitives dodging a Hanoverian army; and later the wholesale expulsion of thousands of tithed farmers and small-holders forced from their family land under the ‘Clearance’ orders.

The Clearance folk became the ‘Crofters’, a class of people forced to make a living in the most challenging places, often in the most unfortunate circumstances. Forget the whiff of romance in early photographs of these people – life was hard, cold, malnourished and thankless. Until recently many would have had no telecommunications, reliable access to social services, or exposure to a developing world. But it’s crofting – a lifestyle alien to most.

Homesteads on the Western Isles

Above: Peat turves harvested from a mire on a June day. Long gone are the natural forests, so this high-carbon fuel is all that is available [and free] to most in crofts; but it’s a slow process waiting for heather bogs to form, and requires careful management so as not to over-dig the deposits. Peat burning is probably the most uneconomic form of fuel – far less efficient than coal, and its CO2 footprint is embarrassingly out of proportion – but how can you convert a crofter who, for a few afternoons of summer digging, can secure a season’s warmth? The ‘con trails’, or ‘vapour trails’ as you might call them, mark a transatlantic route out over the extremities of Scotland. Looking down on these quaint sunlit isles with dotted fields and bobbing fishing boats from 30,000 feet, it’s hard to imagine what those in Business Class might make of the great climate debate.

Houses that ‘must have been’ once, or look good on AirBnB today

Visitors invariably find their way to Loch Na Keal – a pilgrimage to see the White Tailed [Sea] Eagle and hopefully Otters. The loch is really a large inland sea – tidal and very wide. It’s here that the Eagle, [quite the biggest bird of prey in Britain], has made one of its strongholds, nesting in the wild woods up on the rugged hillsides overlooking a world of open water. Daily they hunt somewhere on the 150 square mile tidal expanse. You might be lucky and see one, with patience you might see a pair. With luck and patience you could see much more.

This beautiful stretch of inland coast is just so inviting – and literally makes you buzz with expectation. Somewhere, up on the horizon, or down on the glassy reflections of the sea loch you might get a view of a bird that, with wings outstretched, appears larger than you ever imagined. The adage about silence and patience could never be truer. Both seem to make things happen and that’s the reward. Maybe it’s otters in the swell, clans of oystercatchers probing their way along the shoreline, or red throated divers moving stealthily through the tidal surf – it’s a round the clock drama that only needs your time to appreciate.

Visitors will tell you it’s of course the Otters and Sea Eagles that score high points in the ‘Eye-Spy’ books about the island; but it’s almost impossible to not get mugged by Shortbread, Tweed, Haggis and Tartan Placemats. And of course whisky. Scotch has become a lure in every tourist destination.

The distillery on Mull is a little building at the edge of the Tobermory harbour which proudly announces a production pedigree dating back to 1798. It’s a small establishment with some copper shapes visible in the upper windows, but what’s more noticeable is the constant hiss of steam jetting out from an upper orifice. I don’t know much about whisky and its making, but for the worldly place Mull Scotch boasts, it tests the mind to imagine it all comes out of this little place on the seafront. Maybe the steam is just for show?

Gin from the Glen? A little sidetrack

When I looked at the ‘Tobes’ website – and confirmed my age and email; I was taken aback to see that about 50% of the current site is devoted to gin. Any gin fancier will know that the spirit has undergone a spectacular resurgence in recent times – in part due to the unlocking of the 19th century regulations about the volume of liquor you are permitted to distil. Back in London, in Mr Johnson’s time, gin was easily available, cheap and more importantly, potent. ‘Mother’s Ruin’. The authorities tried to clamp down on back street distillers and it was only licenced to outfits that could produce the stuff in sizeable volumes.

The lifting of this law recently (in the 1980s), made for a great opportunity to brew the liquor legally on a smaller scale with an effort to personalise the output – harping on about the choice of blends and ‘botanicals’. Once upon a time gin was known as a Navy drink, and it was traditionally associated with the epithet ‘London’ or ‘Plymouth’; but no longer. Gin is made everywhere in the UK, everywhere, it seems, where there is the enterprise to do so.

What’s interesting here is that Tobermory Whisky makes gin, as do a host of other traditional Highland distillers. The ‘why’ is straightforward – in a Whisky distillery there is equipment that lies idle for a long time in between batches of Scotch. A ten year old malt spends almost all of its time in wooden casks offsite – so all that stainless steel distilling ‘plant’ remains unused… so why not make gin on a quick turnaround? A ‘catch-crop’ that takes hardly any time. The current market for gin says: ‘YES!‘

There come great weather days in Scotland that make the place memorable – calm clear conditions most welcome after a period of ‘unsettled’ weather. Locals just shrug when the cloud is down to the height of the tallest trees, or wind whips salty spray up into your face as you watch for an otter bobbing around the shoreline.

Even at the height of summer bad weather can make it hard to believe that ‘holidaying’ is possible, but a resolute look and the promise of a change in fortunes will alter things. In summer there’s 17 hours of daylight – a twilight, and no real darkness. In winter its the opposite; precious little full daylight and long nights.

Archaeologists say that Mull was first inhabited in an eon before recorded history. Like much of remote Western Scotland, the area was clearly of appeal with fertile grounds and leeward protection. Settlements on neighbouring Lewis, and further North in Orkney have been dated as being 5000 years old. Older than Stonehenge and the pyramids at Giza. Searching the horizon for more distant islands you can convince yourself that the weather in those days must have been kinder. Did the Christians from Ireland know this?

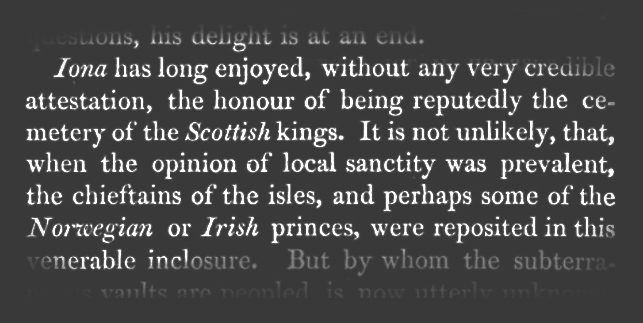

Perhaps the story of early settlement on these islands should be told through their association with Christianity, for it was on the tiny island of Iona, floating just off the west coast of Mull, that St Columba and his companions came in AD 563. A monastery was established and it was from here that the word of Christ was carried onto the mainland and throughout the North. The rest of course became history.

On a good day Iona is bright and colourful, with the few hundred yards of sea crossing looking like the Mediterranean. On a not-so-good day it looks like any other drab island. To the modern way of thinking, Christians must have seen the place on a fine day, and thought God had chosen the place for them; but theologically speaking, and in Latin at that, ‘God’s Calling’, probably counted for more than sea colour or fishing potential.

The settlement was harried and plundered by the Vikings and other Norse peoples – often with the ritual killing of the ‘Fathers of Christianity’, on the beaches in front of the Abbey. For a place the size of a golf course, Iona’s history is certainly long and at times – tortured. It’s said to be one the most visited spots outside of Scotland’s major cities.

As you end the circuit of Mull, its inevitable you’ll find yourself back in the friendly bay of Tobermory. A harbour sanctuary more than adequately kept from the Westerlies. There’s only really one road into the ‘town’, and suddenly you are on a quay and harbourfront that stretches away from you in a large even crescent. Each of the buildings along the front is daubed in chocolate-box colours. A Farrer and Ball swatch*. The highest [and predictably the dullest] building is the church, but in bright pastel there’s a Balti house, 2 hotels, a tackle shop, museum, chandlers, a chocolatery, Co-op, Charity outlets, bank, and of course gift shops.

* F&B = trendy London Chelsea paint manufacturers

Around the harbour itself there’s an overpriced ‘Bar’ with rooftop terrace, some form of car repair business [that clearly does boats too], and a very expensive-looking outward bound shop. The sort from which you might make an impulsive buy after a wet morning on a trail – only to hang the thing in your spare room a day later.

There’s no paint shop along the colourful esplanade, but you are left wondering about the choices people make when it comes to colour-schemes. Is there a Parish Council that puts National Trust ‘approved’ colours in front of a tenant who might be thinking of freshening up their frontage?

Somewhere there’s some hackneyed quote about ‘whatever the weather’ or ‘there’s no such thing as bad weather – it’s down to bad clothing’. In Scotland it’s true that bad weather tests your clothing – and patience. However, after 2 booked-out summers, its hard to imagine the Covid staycationers being put off from such a spectacular world because of midges, oncoming vehicles or over-priced Whisky.

And least of all, the weather.