I’m back in 2006 with a story that was my embryonic effort at producing a web post – but back then I didn’t have a domain name, and the tale was only ever presented as a school AV presentation. 32 pages of photographs and captions. It’s a story about the The Iron Harvest – the deadly legacy of unexploded World War 1 ordnance that still gets unearthed yearly by agricultural activity, road builders or construction projects. It’s a journey through some of the Somme’s historic sites, and what it’s like to walk through places that haven’t been touched since the Armistice over 100 years ago.

The story of course is incredibly complex and it’d take an age to do justice to one of the most terrible engagements undertaken in ‘modern’ warfare. What I’ve included here is a short account of our visit to the region in 2006, and taken the opportunity to elaborate on some of the things we discovered during our short stay. Since 2006 the internet and material available on it has changed the way anyone would research and write such a story. If I’d had the Worldwide Web available freely in 2006 maybe I’d have looked into some of the stories below in more detail…

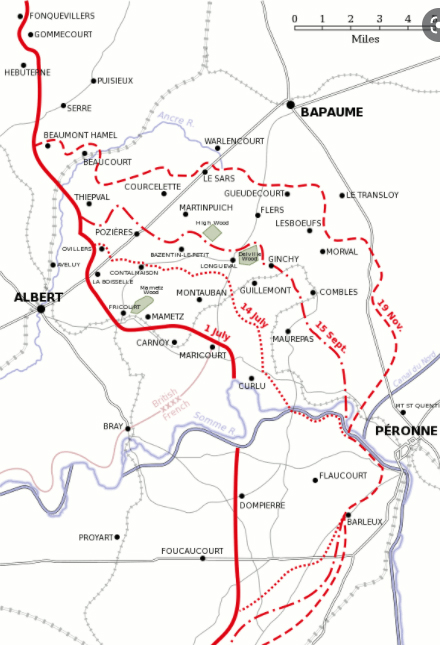

A map that shows the modern look of this part of Northern France. The Somme offensive was fought within a relatively short distance of the marker.

The idea for our trip actually started in early summer of that year, when I went to the region on a cycling tour with a group of friends; with the organiser choosing a route through the historic battlefields of the Somme. Why this location, I’ll never know – but previous years had seen us cycling through other parts of Northern France, venturing into areas of Normandy and along the Landing Beaches of the Second World War. Maybe standing by a burnt out bunker on Omaha Beach or looking over a holed Tiger Tank in a field where it perished, gave us the inspiration.

So, later in the year I decided to return to the Somme region with my two sons – the older of which I think was due to do a History Project ‘living something he’d experienced’. We went back for the Autumn Half Term – just over 90 years after the massive offensives of July 1916. The trip was a marked success as it was made easy for visitors – maps, car parks, galleries, memorials, cemeteries and of course the chance to wander in the exact locations where the conflict took place. To a 13 year-old finding real evidence of the war so long gone was a huge incentive. Here’s some of what we found:

No more than this sign denotes the scene of one of the most bloody battlefields in modern warfare. Today La Boiselle is another village in Northern France with a polite invitation not to exceed the 60 kph speed limit.

The map shows that the the ‘Front Line’, on July 1st 1916, passes exactly between us. La Boiselle.

Nearby, The Lochnagar Crater;

… produced by a massive underground mine explosion on the morning of July 1st 1916. Despite the momentary chaos and distraction it caused, the advancing British troops found it more of an obstacle than an advantage, so the following hours of the battle proved to be futile as hundreds died trying to reach the rim or move around it.

The explosion was a result of the detonation of over 60 tonnes of high explosives carefully arrayed in tunnels under the German front line. At the time it was the largest explosion ever created in human history, and said to also be the loudest. Some say it was heard in London 175 miles away. The result was a crater 30 metres deep and over 100 wide. Today the site remains a war grave with the bodies of hundreds of soldiers still buried under the massive mounds of shifted earth.

As inscribed, this man had no proper burial until 1998 when his boot, and then the rest of his body was unearthed on the path that visitors use to visit the Lochnagar Crater. He probably died minutes after the massive detonation here at 07.28 on July 1st 1916.

George’s memory was put to rest in a 1998 account by a visitor that stopped on the path to examine .303 rifle bullet lying on the surface: ‘Scooping the earth carefully away revealed a boot, in remarkably good condition, when I looked inside I discovered the bones were still in them. The French police investigated the site, and when it was established it was a WW1 body, the Commonwealth War Graves commission were called in to excavate the remains.’

After a few weeks the CWGC [Commonwealth War Graves Commission] produced a copy of the report on the excavation:

”One human body consisting of broken skull, jawbone, teeth, vertebrae, limbs, ribs, pelvis, hands and feet. One pair of Army Boots, 100 bullets. One rifle, with bayonet wire cutters attached… one pair of scissors, two pocket knives, hallmarked pen holder with inscription, and shoulder title TYNESIDE 3 SCOTTISH one folding razor inscribed G Nugent 1306.”

Up-to-date records on the internet show that George Nugent had left behind a wife and a 1 year old daughter. That daughter married and but never had children. She died in London in 1987 without knowing what had happened to her father.

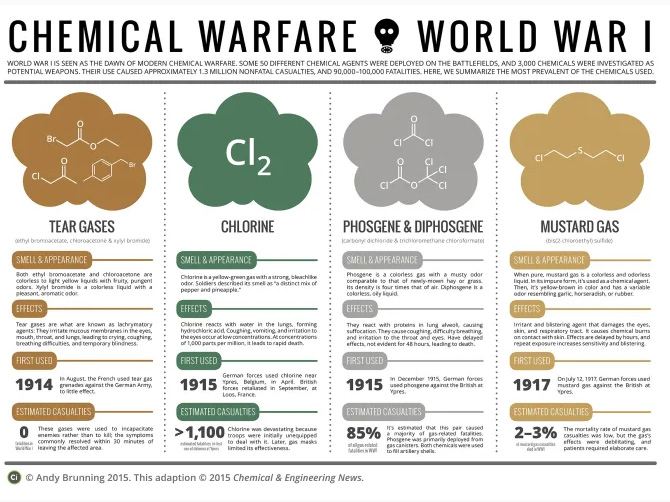

More shells on the roadside. Statistics show that a huge percentage of Ordnance never actually exploded – possibly due to the engineering tolerances of the day, but probably also due to the makeshift style of munitions manufacturing in a time of crisis. I wrote that in 2006, but after looking up a load of gumpf about the ‘Dangers of the Iron Harvest’, I learn a lot more: The stuff that the farmers drag up every time they till the land hardly ever proves to be dangerous – the detonators and chemical makeup long since corroded beyond viability. 90 years in damp mud renders them harmless; unless they are chemical shells. If this is the case they are suddenly extremely dangerous. The farmer doesn’t leave these on the roadside – he phones for the men in protective clothing.

Gas

It was in 1915, in the Ypres salient, that a German scientist called Fritz Haber eventually persuaded his command and those impatient for gains in the offensive, to deploy his ‘brainchild’ of using chlorine gas as a weapon. It took weeks for the right wind to blow across the Allied trenches before he released the ‘yellow hell’. What ensued was a terrible death for the troops ensconced in the opposition trenches as no-one perceived the dangers of the new threat. Chlorine gas drifted and sank into the lower ground where the troops hid from enemy guns.

Chlorine, Phosgene and Mustard gas, were used in all the major WW1 battlegrounds, and these chemicals can remain unaltered [stable] with the passage of time – housed in corroding metal canisters and shell heads. 100 years on they are just waiting to be released with deadly consequences when a bomb case finally rots or is accidentally fractured by a mechanical implement.

That terrible action in April 1915 marked the start of ‘modern’ chemical warfare, and the death or injury of tens of thousands of troops in the WW1 campaign. In itself the use of the German gas that day gave no advantage at the time – they didn’t comprehend just how effectively they had destroyed several miles of front line forces. What it did do was galvanize the opposition into creating its own response. And that, has now, of course led to Chemicals being used covertly, inadvertently, naïvely, cynically, illegally – however you think of it; for all the years to the present day. Chemical Weapons were borne. Despite Geneva.

Somme terrain today and 1916

Above: Where the Front Line would have been on July 1st, looking towards Fricourt and Mametz. Despite being one of the most shell-scarred landscapes in the campaign, modern farming has, over the years, produced a look of normality. Normality by modern farming standards – 100 years ago this area would have been criss-crossed with tracks, hedgerows and small fields.

An unexploded British 18lb shell found on the roadside near Contalmaison. It’s at this point that I’ve done further reading about how and why these fields are littered with unexploded stuff. A ‘Dud’ may have many meanings in the English language – but in WW1 it mainly pointed to only one thing – a shell that didn’t do what it was meant to… Modern statistics show that British Ordnance was far from sophisticated at the start of the conflict. Much of what was initially used, dated back from the Boer campaign and proved inadequate at breaking barbed wire and killing the enemy that were already in a trench. As the campaign progressed it was recognised that High Explosive [HE] manufacture needed bringing up to speed. That included the detonation process which was – as recorded at the time, woefully inadequate, with a danger that armaments being fired from allied lines could go off prematurely because of over-sensitive detonators. The web now recounts stories of artillery batteries that sustained hideous injuries in the firing of shells that exploded milliseconds after firing.

‘In 1916, during the First Battle of the Somme, these ‘prematures’, as they were called, occurred in around 1 out of every 1,000 shells fired. In some divisions during the Somme Offensive, 500 rounds were fired every 24 hours, thus, on average, one ‘premature’ was occurring every 2 days or so. The effect on the morale of the gunners of this macabre game of ‘Russian Roulette’ can be readily imagined. Also, it is not difficult to presume that some gun-crews took the initiative to reduce the frequency of these explosive incidents by de-activating or removing the fuse before loading the shell into the guns.‘

In short, gun crews were able to deliberately tamper with the detonators, and probably set aside periods when they knew their missiles were ‘duds’; and others when they carried on firing ‘primed’ ordnance but kept their heads very low.

A farming landscape shaped by modern technology

Below one of the most fought-over grounds in the conflict, hard to imagine now how nature and farming has run its course.

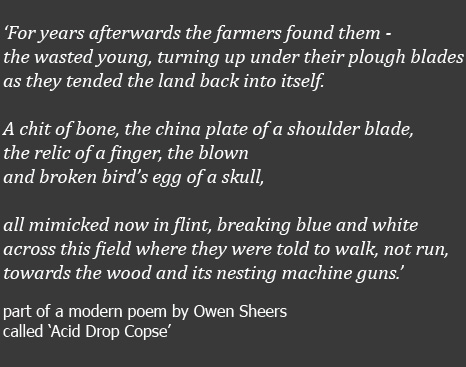

Above is a view looking towards the tiny Acid Drop Copse and, [out of sight], Mametz Wood. These fields are more than littered with the ‘Iron Harvest’. They clatter with it. Despite the decades, modern farm machinery still unearths large amounts of Ordnance that is just left roadside for the authorities to clear.

Acid Drop Copse – a story that leads to another story

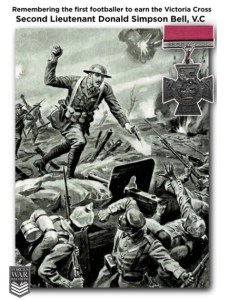

Above, a 1916 picture of Acid Drop Copse. I can’t find the precise reason why it was named ADC; but you can guess ‘trench humour’ had a lot to do with it. Neighbouring emplacements bear the names ‘Death Valley’ and ‘Bell’s Redoubt’. I read on, and find Bell was 2nd Lieutenant, Donald S. Bell, VC, 9th Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment. A VC was won here in this tiny patch of woodland still littered today in 2006, with bits ‘n’ pieces of the campaign. More on Bell reveals he was a teacher and professional footballer from Yorkshire; he survived the 1st July assault, charged enemy machine guns on 5th July, but died doing the same 5 days later.

In 2006, walking through this piece of innocent-looking farmland at the edge of the woods, it took no time for us to find a helmet, barbed wire remains, and a splintered gun barrel. Those were the bits we recognised. Hard to imagine really. Recently others must have been drawn to the area – through lost relatives, a curiosity similar to ours, or a person wanting to put the right things in the mind’s right place.

Albert – a town that was in the midst

Below another ‘find’ on the roadside outside Albert. A shell that could be German and had been fired at the Allied front line that was stationed there in mid 1916. Note its detonator is missing, which would point to it too, being ‘a shot that died with a fizz’.

A place called Hamel

Historical records and veterans’ accounts pinpoint this tiny ‘no-place’ as the epicentre one of the most intense conflicts of the campaign. Ironically, I read that it was known English King Henry V led his army through here in 1415 shortly before the remarkable battle of Agincourt, where tactics won; weight of numbers lost. The loss being that of the the French army, an army that had outnumbered its opponents heavily. The Hundred Years War, or the Agincourt episode, were already 400 years in the past by the time the Western Front became the scar on the psyche of all those who served in the Somme Campaign.

At the time of the July Offensive some of the enemy lines in the Hamel section were defended by the 16th Bavarian Division. A ‘hard Corps’ that had served in Verdun in 1914 and survived; despite hideous losses; [4 in 5]. Historians will point out that at times the Allied ‘frontline’ and the German enemy were never more than a few yards distant [what about grenades I ask..?] – opposing trenches hardly a stone’s throw apart. It was common in some zones. One of those hunkered down in the Bavarian trenches during this offensive was a ‘runner’ that had more than proved his worth. A runner called Adolf.

History, History, History. This junior-ranked ‘no-body’ wasn’t really appreciated or liked, during his active service, but he did get into character and carry the instructions for the regiments. Witnessing slaughter on a large scale, human suffering, and the desperation of warring under the orders of people not entirely connected to The Cause. Wounded twice, but stubbornly clear in his ambition; hospital recuperation and continued bloodshed fuelled Herr Hitler into becoming one of the new angry and disenfranchised Germans at the end of the First World War.

The village of Hamel as seen from St John’s Road. No ground was gained on this hamlet during the first day of the offensive, despite the loss of thousands of British troops.

The Newfoundlanders

Beaumont Hamel was to become an indelible scar on the minds of troops involved in the Somme Offensive. Today it’s hard to imagine the world that existed here throughout the 2nd part of 2016. To the folk of distant Newfoundland, the death toll was unimaginable. People in a far off, far away place, had done ‘their bit’, and now hardly anyone was coming home.

French, Canadian and Newfoundland flags on the Auchonvilliers/Hamel Road. Right: one of the support trenches that was occupied by the ‘Newfoundlanders’ at the start of the offensive. The ground has remained untouched since the Armistice.

Crater-land in the Newfoundland Memorial Park. The Canadian forward positions were in line with the trees.

An account below from the day’s [July 1st] progress. It was some weeks before the sense of total military failure was to cross the Atlantic.

‘…The attack was a devastating failure. In a single morning, almost 20,000 British troops died, and another 37,000 were wounded. The Newfoundland Regiment had been almost wiped out. When the roll call was taken, only 68 men answered their names – 324 were killed, and 386 were wounded…’

Walking up the supply trench [seen in aerial pic above] to the front line. Newfoundland Memorial Park. Shell craters are no more than a few yards apart.

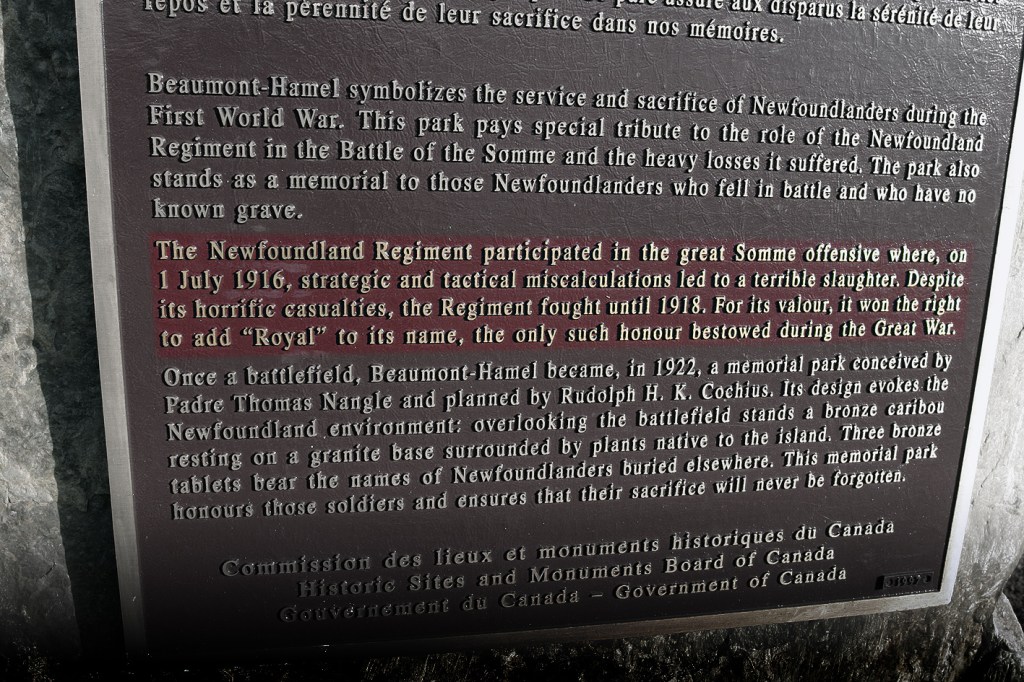

Detail of the inscription to the Newfoundlanders. A quiet windswept community back in one of the most remote parts of the Northern Hemisphere – of ‘The Empire’, must have found the reality of this unbelievably hard to swallow.

The Y ravine, Hawthorn Ridge and the 51st Highlanders

The perimeter of the infamous Hawthorn crater and Y Ravine. No-one has excavated this site which must still contain the remains of hundreds of soldiers and thousands of pieces of military hardware.

Distant horizon behind the line at Auchonvilliers. It was from here that artillery batteries bombarded the German trenches on a daily basis.

Casualties of the assault on Y ravine, an objective that was not taken on Day One. Nearly 30% of those involved were killed.

51st Highland Division Memorial, Beaumont Hamel. The Highlanders finally took their objective on November 13th, 1916 – 135 days after the assault began. They suffered terrible casualties in gaining only few hundred yards.

Memorials

The Memorial at Thiepval. An edifice designed by the eminent architect [of the time] – Sir Edwin Lutyens. It was completed some 14 years after the Armistice and painstakingly records the names of over 72,000 Allied troops who were never found or identified after the Somme Offensive.

For years after the battle, volunteers had the gruesome task of finding, identifying and burying the remains of tens of thousands of men who had died in action. Many were found in makeshift graves that had been dug in the heat of the conflict – often with very little left by way of a recognisable human form due to decomposition or the terrible injuries suffered. All have been accorded full military honours.

Years on, after my initial 2006 story, ‘lost’ soldiers – like Private Nugent [Lochnagar Crater above], have been regularly un-earthed and in many cases, identified by modern means. The plaques on the Thiepval register have in places been ‘filled-in’ where a known find has been buried elsewhere.

‘Inconnu’ – ‘Unknown’ in French; a sad epitaph seen in every one of the Somme’s 175 cemeteries. Every inch of the Somme region lies in French France.

Ovillers Cemetery looking towards La Boiselle and Lochnagar. There are cemeteries every few hundred yards in this area. None looking any different from the next.

Ovillers burial ground seen from La Boiselle. This small patch of a once agriculturally fertile field contains the remains of 3500 people; of whom over half have never been identified.

In the distance the ‘Sunken Road’ Cemetery near Contalmaisin. The resting place for 214 soldiers whose Company successfully cleared the valley after a month of stalemate. They gained just over 100 yards of ground…

An unexploded British shell on the roadside at the ‘Sunken Road’, near Contalmaison. Detonator cap still in place means that this bomb is still potentially lethal. How many years will pass before the ploughman gets an empty ‘pass’ as he tills these fields? How many more modern folk [100+ years on] will be connected enough to feel that the open fields and reconstructed woods of this part of Northern France represent something to them. Something that ended so many years ago?

Same place names 100 years on – stirring the imagination, but surely starting to lose their meaning as time goes by? It’s hard to think of the future of these theatres of war, or the spaces they occupied, without ‘living’ witnesses. Wikipedia has a strange reference page listing the oldest survivors of World War 1. By the time of our visit in 2006 there were only 13 individuals recorded. These were just veterans, and it doesn’t explicitly detail where they served. By 2011, that was it – the last were gone and the voices of those who took part in the Great War were gone forever. How long will it be for the Iron Harvest to be consigned to history?