Passing Places Only

Places that take time to get to – Scotland’s Islands; CalMac Ferries and 9 Distilleries. Jura, Islay and The Hebrides. Summer 2022, Westminster in upheaval, fuel prices rocket, a war in Ukraine, and record Summer temperatures.

Scotland has many ‘A’ roads that are no bigger than farm tracks – all relying on the driver’s code of understanding that they are Passing Places Only thoroughfares. ‘B’ roads are virtually the same but with less traffic and fewer passing places.

Above: The road to Kilchoman, Islay. Here plenty of warning of oncoming traffic but nowhere to pass.

Below: ‘The Geocrab Loop’, Isle of Harris.

Below: The Driving Experience – On the Uig road, Lewis.

A sped up view of the trip from a place called Miavaig to Uig Bay on Harris.

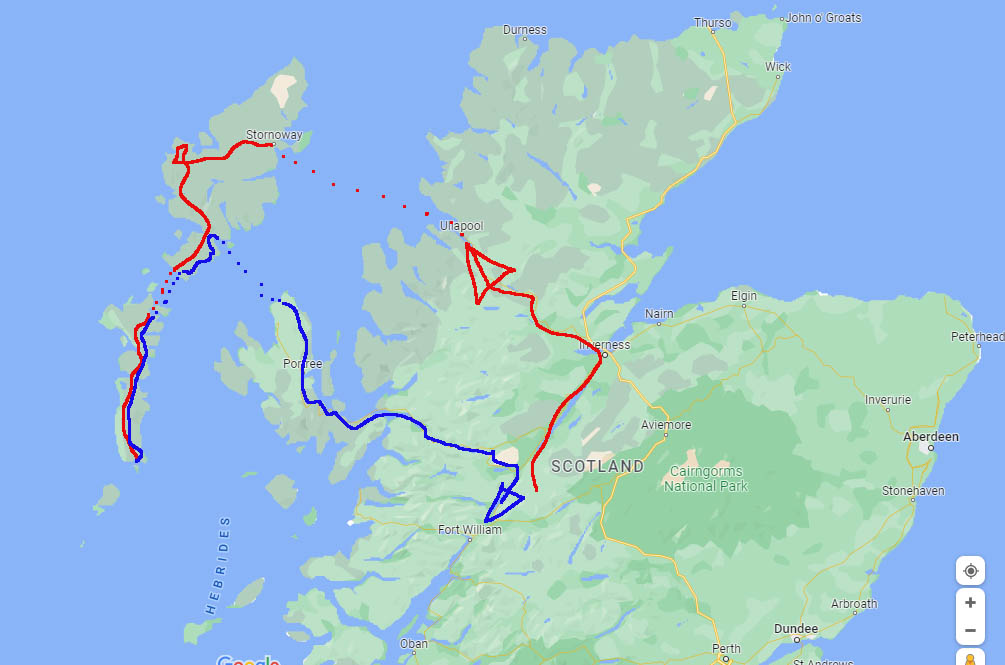

A route to the Western Isles? Red up; Blue down.

CalMac

Tell anyone in Scotland that you’re using CalMac to get about and they’ll roll their eyes but know what you mean. Caledonian Macbrayne is a state-owned public ferry service that reaches out to all the inhabited isles. Its coverage, entirely on the West of Scotland, is impressive. There are 35 regular year-round services with more added in the summer season.

Above: The Port Ellen to Kennacraig service. 2hrs 20 minutes to connect Islay with the Mull of Kintyre. To get to Glasgow it’s either 2 more ferries across Loch Fyne and the Firth of Clyde, or 3 hours plus on the infamous ‘Military Road’ which is subject to very sudden closures due to extreme weather.

The map, but maybe not the detail, showing in red the reach of CalMac’s service. On a calm day this looks equable, but in Scotland there are at least two ‘not calm’ days to every one that is tolerable.

To a visitor CalMac provides what seems like a streamlined service across dozens of routes – the longest journey being around 5 hours, the shortest a mere 5 minutes.

Locals are all too prepared to complain that the summer spaces are often taken up by trippers in big RVs, who’ve often made a booking months in advance. Come winter many routes aren’t run so regularly.

Above: The 20 minute hop from Mull to Lochaline on the Corran peninsula.

Below: A single full-sized tanker is taken back to Islay from neighbouring Jura. Roll on – Roll off. 10 minutes all done.

Many services are there merely to enable you to avoid driving long overland distances. Scotland’s Western sea lochs stretch far inland, meaning the ‘long way round’ could be 3 hours’ driving instead of 45 minute direct crossing.

Above: The Corran ferry – distance equivalent to 2 good golf shots with a 1 Iron, or about 2 hours going inland and around nearby Fort William.

Above: The Berneray jetty & plotting a careful route through the treacherous shallows between the Uists and Harris.

The Country comes to a standstill…

A slightly bizarre moment. At exactly midday on 19th September 2022 this ferry stopped its engine mid-journey for one minute to observe the silence being held during the funeral service for HM Queen Elizabeth. Somewhere in the middle of Loch Fyne. Passengers and crew alike remained observant, and minutes later we disembarked at the port of Tarbert.

Coming alongside a big one. The tiny Jura service negotiates jetty clearance astern the regular service from the mainland.

Below: Steaming out of Ullapool into the Minch on a grey morning. This twice daily service takes two and a half hours and costs a mere £80 for a car and passenger.

Remoteness

Just off the ‘A’ road… Possibly one of the most isolated regions of the Hebrides. A croft farm on Lewis. This is a terrain that is mainly sodden peat mire; inhospitable and midge-ridden in summer; and in winter endures constant wind, long nights and heavy rainfall.

Remember, when you moan about your 1st Class postage costs next Christmas, someone, somewhere out there, can post their greetings cards for the same price as you might do on a street corner in suburbia*. That’s subsidising isn’t it? Amazon, and similar courier services, politely state on their websites ‘UK Mainland delivery: Standard – but other postcodes may incur extra charges’. They do here.

*

An Asian Scottish Post Office worker on duty [on his phone] on the Askaig to Jura ferry [which incidentally takes 10 cars and 10 minutes.] His ’round’ some days includes a 40 minute trip up a single track road to deliver to the remote hamlets of Craighouse; or further to Ardlussa. Then 40 back with whatever post that needs to get to the big wide world.

Animals

Above: What you see is what you get in a passing place – luckily no oncoming traffic. An aged Blackface sheep, and, offspring?

Blackfaces enjoying a long June day. Beyond them the Atlantic, and nothing else before Newfoundland.

Road hazards that don’t always budge.

1:25,000

A road that became a track that became nothing. Perhaps once a drover’s route across the Kneep peninsular, but it was on my map! I was taught to trust Ordnance Survey mapping; I learnt how to read it at school and appreciated the accuracy of the 1:25000; but this detour was too much for my van. Stretching into the distance the track deteriorated further until it was only fit for young people with walking boots.

A Harris road that was on the map, and lead exactly where it said it would – around the Finsbay peninsula to an oddly named place called Geocrab.

Beaches and Skies

Luskentyre, a wild setting for a day on the beach. Below the same beach on a different day plus a bit of HDR.

Above/Below Nisabost and Silabost – Gaelic names meaning ‘Nisaplace’ and ‘Silaplace’. Not much to it really…

More beaches and hardly anyone to enjoy the 14C water and fresh breeze.

The spectacular tidal wash at Leverburgh, Harris.

Whisky

Sheep and subsistence farming may have been the main economies in the Hebrides until the arrival of tourists and possibly the fad for distilling something that characterised your particular flavour of peat. In the Outer Hebrides there is only one distillery which proudly plugs its ‘own brand – own flavour’. But upon research there’s a couple of things to note.

Point 1: The new Harris Distillery is only in its infancy and CANNOT sell its whisky until at least 5 years old – so it’s not yet up and running. In the meantime it uses its metal stills for ‘quick turnaround gin’. Outrageous you might think, but otherwise the makers’ kit would lie idle between batches of Whisky that must spend most of its time ageing in cask. Gin, albeit 650 miles from its naval heritage birthplace, sells well when presented in funny bottles coupled with a few lines of marketing guff about ‘botanicals’.

Point 2: to add to the marketing and credibility claims of the Harris Distillery, I learn that the ‘aged wood flavouring’ relies on bought in sherry casks from Jerez in Southern Spain. A lovely business plan to me, as I frequently drive past the M. Martin Xerex Bodega as I take my son to school in outtown Jerez…

Peat

Landscape of granite. Thin soil and not much will grow – except where the peat deposits have built up over the eons to form mires often several feet thick.

Above: Peat in its purest form – hundreds of years’ worth of deposits – still being burned for heat, used to roast and smoke in the Whisky process, and sadly bagged up for gardening enthusiasts.

Above: probably one of the most valuable ‘dribbles’ in the story of dribbles. The inconsequential stream that flows out of an inconsequential peat bog at a place called Craighouse on Islay. Bottle by Bottle this fills the Jura Malt distillery.

Bog Asphodel. A plant that likes this place…

Machair

Machair is a Gaelic word meaning “fertile plain”. It’s a word now widely used to describe these fragile pockets of fertility. Here, one wide stretch of grassland, with its particular variety of herbs that make this thin sandy soil almost attractive to the subsistence living. On a good day that is.

An RSPB notice. Little Terns are susceptible to the slightest imbalance in the environment. Machair is ideal but doesn’t look like its much help when grazing cows lumber by.

Cranesbill and viola creating an edible carpet.

Buttercup, rock rose, flag iris and ragged robin looking out to the Isle of Vatersay and the resting place of the SS Politician, the ship that gave its whisky to the islanders and a smuggling legend to the world. ‘Whisky Galore’.

A Chess Find

Some time in the summer of 1831, a man called Malcolm MacLeod found a collection of carved chess figures in a small stone chamber in the dunes at the head of his local beach. There were 82 pieces of intricately carved walrus ivory. Much debate followed about their provenance, and indeed whether there were others waiting to found. What is remarkable is that these carvings have been dated back to the 12th Century when this part of Scotland was under Viking rule.

The real thing in an Edinburgh museum, and a plastic version in a Stornorway gift shop.

No-one knows where the chess men were actually found – none have been found since.

Otter Territory

A difficult creature to see, although there’s always someone on hand to tell you that you’ve just missed one. An ideal bay on an ideal day at Berneray on North Uist.

Below: Sighted – 300 yards away! That could have been it for the day, but when least expecting it, I caught sight of this beast harbourside and took a picture from the bus shelter. A second later it was gone. Luck with otters…

A hard place to be

It’s obvious looking at life in these islands that survival can be hard work. It’s also a landscape that seems to have been afforded little time for the inhabitants to clear up, as many places have ruins and signs of dilapidation that simply goes on unchecked. Outbuildings and spent farm machinery are no exception here.

Above and below: There’s Lewis & Harris. Lewis is often described as the more hospitable of the two islands – in landscape terms. Harris is often spoken of in the same breath as Tweed and not much else. What to think? Its obvious on a tour around the small loop roads on the Isle of Harris, that its a mixture of Moonscape, hardship and Airbnb.

Global Fame?

Distilleries on remote islands

Islay and Jura – 2 names synonymous with Scottish Single Malt whisky. Little island worlds. Not that far from the mainland, but nevertheless a world away.

These islands I visited, and did a ‘not completely committed’, whisky trail; visiting 9 of the 9 but not dawdling in the inevitable ‘Visitor Centres’. The world enjoys the produce of these tatterdemalion shacks that produce the golden liquor; visitors come in their droves to try the malt – maybe standing in the peat bog that flavours the drink. Distinctive buildings with sky high chimneys, and copperware all over. Someone, sometime in the 1800s, cleverly got onto something about distilling a liquor from a blend of what was readily available from the peat bogs at the back of the house.

The tale of Whisky is undoubtedly long and complex. Claims are made for its origin pre-dating bagpipes, highland clearances and of course the taxing English down South. Here, 2 rocky islands where it hardly stops raining. 2 outposts of Western Scotland facing everything that the elements can conjure; a place where the cloud drops, on a bad day to the height of the straggly trees that complete the landscape.

A ‘Dram’, not even a ‘Wee’ one; for an Australian I chatted to – who’d already necked back his share of the very expensive ‘Sample Menu’ at Brunhainbadich. The road back to salvation and sobriety would always have had the Paps in sight. Below.

The Paps of Jura – 2 rocky mounds on which this beef has an all day view. The landscape here is inhospitable, unsettled and full of scenic drama. Jura’s human population is bettered by red deer, birds of prey and very probably visiting wales.

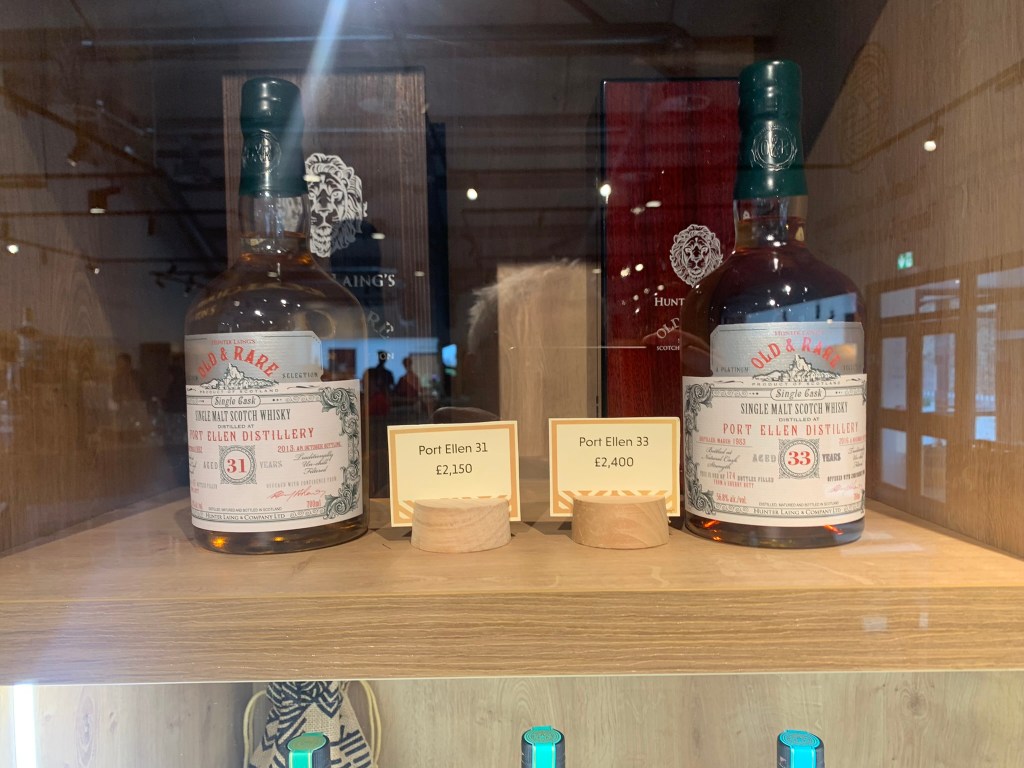

One I didn’t go for. 2+ Grand a bottle. But, and its a serious BUT ; none of this wouldn’t happen if someone wasn’t prepared to pay thousands for whisky. Heritage-curious Yanks, wealthy Dutch, obsessed Asians, or just that class of people with money to prove who they are…

The best or worst sight you could wish for… Leaving Port Ellen and the Whisky World on a rare fine day.

You leave behind island societies that appear to have changed little over recent time, and there’s definitely evidence that for some there’s a reaching-hand grasping back to a pastoral era.

Below: Modern crofts in the traditional style.

Sunset at 11pm on a June day; a golden light that lets the sharp-eyed possibly see as far as St Kilda, the remotest island of the Hebridean archipelago. A now uninhabited outpost where crofting life drew to a halt because of the pressures of the ‘modern world’. August 1930.

I can’t get this text with photos. Must be bad reception here. I’ll try again daytime Monday.

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike